Myriam Ababsa, editor, Atlas of Jordan: History, Territories, and Society. Beirut: Presses de l’Institut Français du Proche-Orient, 2013.

أطلس الأردن - التاريخ، الأرض والمجتمع

Jadaliyya (J): What made you write this book?

Myriam Ababsa (MA): Jordan lacked a synthetic book about its historical resiliencies and social dynamics. The Royal Jordanian Geographical Center published the first two-volume Atlas of Jordan in 1984, but this series was dedicated to the country’s physical geography and lacked any reference to Jordan’s social and political dynamics. In the following two decades, several publications attempted to present synthetic historical views of Jordan, but they remained shy of tackling contemporary issues and spatial analysis (see, for example, Kamal Salibi, The Modern History of Jordan; Ghazi Bisheh (ed.), Studies in the History and Archaeology of Jordan VII; and Thomas E. Levy, Michèle P. M. Daviau, Randall W. Younker, and May Shaer, Crossing Jordan: North American Contributions to the Archaeology of Jordan).

In the start of the last decade, the Institut Français du Proche-Orient started to publish a series of atlases of Middle Eastern countries in close partnership with local research institutions. The first was the Atlas du Liban. Territoires et société, edited by Eric Verdeil, Ghaleb Faour, and Sébastien Velut and published in 2007 (recently translated). The current Atlas of Jordan is the second of this series. An Atlas of the North of Iraq, edited by Cyril Roussel, is under preparation. This is part of a French tradition of producing comprehensive atlases with both maps and texts. Elisée Reclus’s Nouvelle Géographie Universelle was a cornerstone in this field.

In September 2006, I was appointed as a post-doctoral researcher at the Institut Français du Proche-Orient (IFPO) with the project of producing an atlas of Jordan. Based in a multidisciplinary institute such as the IFPO, I wanted to include contributions by most of my colleagues, including historians, archaeologists, political scientists, and anthropologists. It took us nearly seven years to prepare this book with a team of forty-eight Jordanian, European, and American researchers and with the assistance of Caroline Kohlmayer, who beautifully designed the maps. The bilingual dimension of the book was a challenge, especially crafting Arabic text for the technical terms that comprised half of the book. We were also all engaged in other research projects at the same time.

The project began in 2006 with the completion of a geo-referenced database, in collaboration with the Royal Jordanian Geographic Centre (including the acquisition of a Digital Elevation Model, of the Jordan Transverse Mercator projection system, and the purchase of 1:100,000 scale maps that were scanned and geo-referenced). The Department of Statistics was extremely helpful, providing us with the 2004 census for each locality in an excel spreadsheet. We geo-referenced every Jordanian locality for the three censuses of 2004, 1994, and 1979. This allowed us to calculate average annual growth rates for the periods between censuses, grouping communities using the 2004 administrative structure. With the permission of Jordan’s Prime Minister, several Jordanian institutions (the Royal Jordanian Geographic Center, the Ministry of Water and Irrigation, the Greater Amman Municipality, and the Ministry of Municipal Affairs) provided us with geo-referenced files (including roads, administrative boundaries, land use). The work was easier than in other neighboring countries because several databases were already available. Although the chapters on contemporary dynamics were written between 2009 and 2012, diachronic and chronological elements are provided for thirty to fifty years wherever possible.

The project was funded by the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the French Embassy Cultural services. It was supported by the Agence Universitaire de la Francophonie in the form of a university exchange program between the University of Jordan, the Ecole Nationale des Sciences Géographiques (ENSG-IGN Paris), and IFPO. I would like to thank the European Union Delegation in Jordan and the Swiss Cooperation for kindly supporting the cost of the translation in English and Arabic and of the printing of the book.

J: What particular topics, issues, and literatures does the book address?

MA: This atlas aims to explain the formation of Jordanian territories over time, and to present the legacy inherited by the Emirate of Transjordan in 1921. We studied the spatial resilience of old structures, namely the complementarities among land areas (cultivated fields, steppe, and scrubland) dating back to the Neolithic period. We also examined trade dynamics along the valleys (Wadi Jordan, Wadi Araba, and Wadi Sirhan) and inherited administrative systems (urban structures of the first kingdoms of Amman, Moab, and Edom) as well as trade between Damascus and Jerusalem under the Ottoman Empire. Settled populations (ma’mura) fluctuated for centuries across the boundary of dry farming areas, depending on the modes of state control of nomadic tribes and the technical expertise of water supply systems. The pilgrimage route developed along this boundary, along the ancestral route linking the south of the Arabian Peninsula to Damascus, which for centuries was the eastern limit of settled populations.

The atlas has three parts: physical geography (“Jordan’s Physical Constraints”), historical (“Jordan before Statehood: Historical Glimpses”) and “Contemporary Challenges.” The first part presents the unique physical geography of the land to the east of the Jordan River and the Wadi Araba. Jordan and Israel share the banks of the Dead Sea graben, which is the lowest point on earth (423 meters below sea-level).

In the historical section of the atlas, our team studied Jordan’s administrative organization to ascertain whether the territory lying to the east of the Jordan River and the Wad Araba was peripheral or at the heart of a kingdom over time. This determined whether armies and taxes could be levied under the Persians, Nabateans, Romans, Byzantines, Umayyads, Abbasids, Crusaders, Ayyubids, Mamluks, Ottomans, and British. Urban hierarchies were studied to show which fortified towns best took advantage of their situation, to describe trade routes and road networks, and to explain land use (mining, agriculture, and early industry).

This historical section is fundamental to understand social dynamics in contemporary Jordan: how the main tribes and families settled and developed social ties within the region; how the cities of Nablus and Salt, Kerak and Hebron were linked both socially and economically; the major importance of the pilgrimage in the structuration of the territory, with khuwa payments to the main bedouin tribes; and finally, the major role played by western powers in the building of the state. The Ottomans ensured the safety of Muslim pilgrims by paying khuwwa to large tribes. In the early sixteenth century, the territory of modern Jordan had only four hundred villages inhabited by thirty-five thousand people, subject to seasonal attacks by the Bedouin. Before the army and taxation reforms in the mid-nineteenth century, villagers lived in extreme poverty, with barely enough to survive. Their population is estimated to have been 225,000 at the end of the Ottoman Empire, including 103,000 nomads.

The contemporary section of the atlas studies the nation’s population and its geographical distribution. The stability of the Hashemite regime depends on the Jordanian social contract whereby Palestinian refugees are full Jordanian citizens and the kings of Jordan are guarantors of their right to return. The building of the Jordanian nation must be studied in parallel with that of its geographic boundaries, since the definition of nationality is legally bound to the country’s borders. This is particularly the case for the Palestinians, since the 1954 Nationality Act specifies that any person born in the West Bank or in Jordan is Jordanian. Following the royal decision to split from the West Bank on 31 July 1988, only those citizens born in Jordan remained Jordanian; the others became de facto Palestinians.

Since its independence from British rule on 25 May 1946, the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan had covered several territories. It integrated the West Bank from 1949 until July 1988 (occupied by Israel from June 1967), but remained stable for almost a century, despite the challenge of integrating several waves of refugees, mainly Palestinian (forty percent of the population), but also Iraqi and Syrian refugees since 2011 (ten percent of the population). The main reason for this stability is the allegiance of the population to the Hashemite monarchy, which granted full citizenship to Palestinian refugees from 1949 onwards.

Jordan’s population is undergoing major changes in its demography and its family structure. The country started its demographic transition in the 1960s, and has maintained a high fertility rate with 3.6 children per woman in 2007, while the rates in Lebanon and Turkey fell to 1.9 and 2.2.

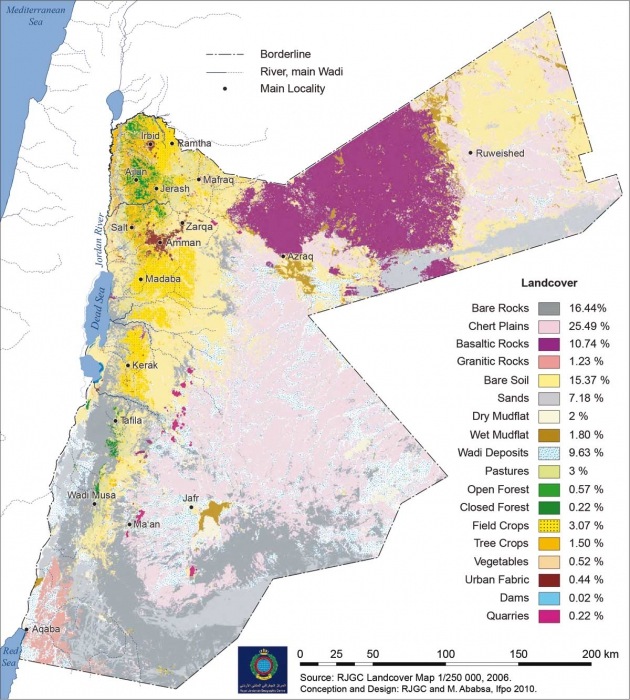

Figure One: Jordan’s Land Cover: A Land of Contrasts

[Myriam Ababsa/Atlas of Jordan]

Jordan is a small country lacking in natural resources and with little useful land area (see figure one). Since the 1970s the country has had a rentier economy. Its income is both direct, in the form of remittances from the hundreds of thousands of emigrants in the oil producing Gulf countries, and indirect, due to its geopolitical position as a pivotal country for peace in the Middle East, which guarantees generous international aid to ensure stability. The main geographical consequence is the concentration of both the population and the foreign direct investments in the Amman-Russeifa-Zarqa conurbation, with half of the inhabitants and ninety-one percent of the capitalization of Jordanian companies. Another consequence is that services counts for more than two-thirds of the economy (71.3 percent in 2010), driven by the tourism sector, followed by transport and telecommunications.

Jordan is drastically poor in energy (importing ninety-six percent of it) and in water (it is the fourth poorest country for water per capita, with 145 m3/capita/year in 2010). To reduce the substantial costs of imported energy and its water deficit, Jordan implemented megaprojects in the sectors of water, energy, and transport at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Thirty billion US dollars have been budgeted for projects over a period of twenty years. The largest project, worth 11.6 billion US dollars, is the Red Sea-Dead Sea canal, which is based on the joint participation of Jordan, Israel, and the Palestinian Authority. Several feasibility studies have been carried out. However, the project is stalled due to the lack of regional stability, rather than technical issues. The canal would require a considerable amount of energy that would be provided by a large civilian nuclear power project, at a cost of ten billion US dollars.

J: How does this book connect to and/or depart from your previous research?

MA: My main research topics are public development policies in the Middle East, both at a regional and urban level, looking at the dialectics between ideologies and social practices.

I first studied the implementation of the Euphrates Project in North East Syria, in the Raqqa governorate, for my PhD in Social Geography, defended in 2004 at the University of Tours and published by IFPO in 2009: Raqqa, territories et pratiques sociales d’une ville syrienne. I studied the developmental ideology of the Syrian regime toward the poor northeastern Jazira. I presented the double dialectic adaptation of the Euphrates tribes to the Baath Party and of the Baath ideology to the tribal realities of this region. As the center of the North East Syrian agricultural front since 1974, Raqqa experienced rapid population growth, and became subject to large-scale urbanization projects that sought to transform this old wintering station for semi-nomads into a model of Baathist development. I studied the distribution of Syrian state farms land to their former owners and workers in 2001, as a form of counter-revolution. I also examined how the local population was dealing with the Shi’i mausolea built by Iran on the tombs of Ammar ben Yassir and Uways al Qarany. The entire region became the heart of the Islamic State in Iraq and in the Levant in 2013, destroying years of social development and tolerance between the communities.

I then had the opportunity of working on informal settlements upgrading policies in the Middle East with Baudouin Dupret and Eric Denis. In Popular Housing and Urban Land Tenure in the Middle East, published in 2012 by the American University in Cairo Press, we adopted a praxaeological approach to popular housing, analyzing daily interactions binding ordinary citizens, public agents, and entrepreneurs.

I was also fortunate to edit a bilingual book on Cities, Urban Practices, and Nation Building in Jordan with Rami Daher, one of Jordan’s finest architects, urbanists, and scholars. Published in 2011, this book addresses the extensively studied issue of national identity and citizenship in Jordan through the lens of urban life, examining the forms of integration and demarcation of the different components of the population in urban arenas. It privileges a diachronic approach focusing on the role of towns in Jordan’s nation building, including the management of urban spaces and the spatial practices of individual urban residents detached from kinship affiliations.

These projects were ongoing while writing the atlas and influenced my writing. This was especially the case with the emphasis given to the analysis of social disparities, the participation in informal settlements upgrading, and more generally the importance of taking a diachronic approach.

J: Who do you hope will read this book, and what sort of impact would you like it to have?

MA: We worked hard to produce a bilingual English and Arabic atlas, with introductions in French. We distributed four hundred copies in Jordan to all the ministries and universities, thanks to the support of the European Union Embassy in Jordan. The Atlas is now online in English and will ideally be online in Arabic too by fall 2014. It will therefore be widely accessible to university students as well as to government employees. We hope this will help better guide the country towards balanced development, with the well being of its people and the preservation of its outstanding heritage in mind.

J: What other projects are you working on now?

MA: As an associate researcher at IFPO, I am working with Luigi Achilli and Jalal Al Husseini on “Forced Migrations and Nation Building” in Jordan. Jordan has the highest number of refugees in the world, both in absolute and relative figures (two million Palestinian refugees registered by UNWRA, and also citizens, and 650,000 Syrian and Iraqis refugees registered by UNHCR in 2014). Our aim is to investigate how the several waves of forced migrations have affected Jordan’s national project. We will consider the policies conducted by the government regarding the several groups of refugees, their legal status, and the management of the refugee camps.

J: How do you see this book contributing to the field of urban studies and studies of urban planning in the Arab world and beyond?

MA: Chapter nine, “City Planning, Local Governance, and Urban Policies” is dedicated to urban issues. It describes the successive urban policies undertaken by the government of Jordan to control urban growth, and develop public services while involving residents, in order to promote local democracy. It also discusses the challenges due to the presence of disadvantaged communities in Jordanian towns and the successive policies to regenerate informal settlements. From 1980 to 1997, Jordan was a trend-setter in the field of regeneration of urban slums in the Middle East, being the first Arab country to apply the new developmental ideology advocated by the World Bank in Latin America and Asia, whereby inhabitants of informal areas participate in all the stages of renovating their home and can become homeowners via long-term loans guaranteed by the state.

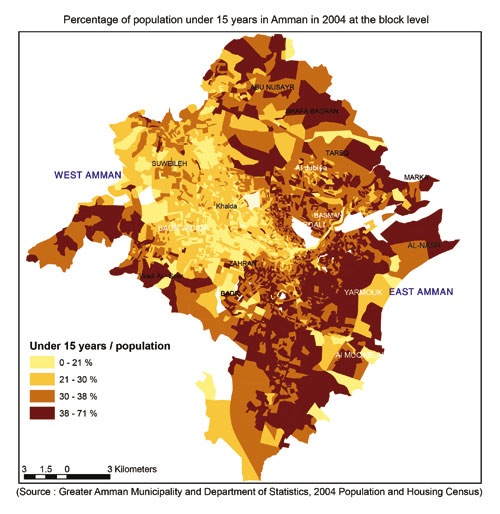

Figure Two: Percentage of population under fifteen in Amman at the block level in 2004

[The figure clearly shows the line that divides East and West Amman. Less than one-third of West Amman’s

population is under the age of fifteen, compared to more than thirty-eight percent of the population of

East Amman (al-Nasr, al-Quweisma, and Khirbet al-Suq districts). (Caption: Myriam Ababsa/Atlas of Jordan)]

An achievement of particular interest in this chapter involved the mapping of social disparities at the level of 4,800 blocks for the city of Amman, in collaboration with the Greater Amman Municipality’s Geographic Information System department. This level of visualization is very rare for the Arab cities, for which ethnographic analysis or urban master plans are more common. For the first time, it was possible to visualize the divide between East and West Amman, based on the family structure (size, number of children, age, and sex), but also employment and type of housing (see figure two). Social disparities are particularly wide within the major Jordanian towns that saw the arrival of Palestinian refugees from 1948 onwards and again in 1967. Large pockets of poverty have developed in informal settlements built near UNRWA camps. These densely populated areas, with insufficient health and education services, are also home to poor foreigners (mostly Palestinians from Gaza with Egyptian travel documents, but also poor Iraqi and Syrian refugees). The series of maps show the major social disparities within the densely populated districts of downtown Amman, the residential areas to the west, industrial areas to the southeast, and rural areas to the south.

Excerpts from Atlas of Jordan: History, Territories, and Society

From Introduction to Chapter Nine: City Planning, Local Governance, and Urban Policies

While Jordan’s urban growth reflects the country’s geopolitical situation, with every war in the Middle East resulting in the arrival of large waves of refugees, the country’s urban policies testify to changes in economic models over the past fifty years: a welfare state, structural adjustments, and economic liberalization. During the 1980s bold policies were pursued to renovate informal settlements with the participation of residents, the Palestinian camps were included from 1997 onwards. However the economic liberalization of the first decade of King Abdullah II’s reign resulted in policies actively seeking to attract Gulf capital to Amman and Aqaba. The flagship project of this liberalization was the new Abdali downtown, launched in 2004 by Mawared, a joint public-private corporation. The Greater Amman master plan presented in 2008 offers international investors land along development corridors, and plans to provide the city with a public transport network with dedicated bus lanes. At the same time, the king announced an ambitious program to build 100,000 homes for the lowest income households. All of these projects were suspended in 2011 amid social and political protests. This chapter describes the successive urban policies attempted by Jordan to control urban growth and develop public services while involving residents, thus promoting local democracy. It also discusses the challenges faced by councillors due to the presence of disadvantaged communities in Jordanian towns and the successive policies to regenerate informal settlements.

***

Si les dynamiques de croissance urbaine reflètent la situation géopolitique de la Jordanie, chaque guerre au Moyen Orient se traduisant par l’arrivée d’importantes vagues de réfugiés, les politiques urbaines, elles, témoignent des changements de paradigmes économiques depuis un demi-siècle : État-providence, ajustement structurel et ouverture économique libérale. Des politiques audacieuses de réhabilitation des quartiers informels avec participation des populations sont conduites au cours des années 1980. Elles intègrent les camps palestiniens à partir de 1997. Mais l’ouverture économique libérale de la première décennie du roi Abdallah II se traduit par des politiques visant à attirer des capitaux du Golfe vers Amman et Aqaba. Le projet emblématique de l’ouverture libérale est le nouveau centre ville à Abdali, construit à partir de 2004 par une société mixte publique-privée, Mawared. Le schéma directeur du Grand Amman présenté en 2008 propose aux investisseurs internationaux des terrains le long de corridors de développement, et prévoit de doter la ville d’un véritable réseau de transport public en site propre. Parallèlement, le roi annonce un ambitieux programme de construction de 100 000 logements pour les ménages aux revenus les plus modestes. L’ensemble de ces projets subit un coup d’arrêt en 2011 dans un contexte de contestations sociales et politiques.

Ce chapitre expose les politiques urbaines successives tentées par la Jordanie pour contrôler la croissance urbaine, développer les services publics tout en faisant participer les populations. Il présente aussi les défis qu’offre aux édiles la présence de poches de population défavorisées au cœur des villes jordaniennes et les politiques successives de réhabilitation des quartiers informels. Le cadre municipal est présenté, ainsi que les moyens d’action des municipalités. Puis, une analyse fonctionnelle et urbanistique des trois principales agglomérations jordaniennes, Amman-Ruseifa-Zarqa, Irbid et Aqaba est menée.

***

ان كانت ديناميات النمو الحضري تعكس الوضع الجيوسياسي للأردن، حيث كل حرب في الشرق الاوسط تسبب وصول موجات كبيرة من اللاجئين، فإن السياسات العمرانية تشهد على تغيرات في المبادئ الاقتصادية منذ نصف قرن: رعاية الدولة، والتكيف الهيكلي، والانفتاح الاقتصادي اللبرالي الحرّ .

طُبّقت سياسلت جريئة لاعادة تأهيل المناطق العشوائية بمشاركة المواطنين خلال عقد الثمانينات؛ وشملت المخيمات الفلسطينية اعتبارا من عام 1997. لكن الانفتاح الاقتصادي اللبرالي في العقد الاول من عهد جلالة الملك عبدالله الثاني ترجم من خلال سياسات سعت الى جذب رؤوس الاموال الخليجية الى مدينتي عمان والعقبة. وكان المشروع الأبرز لهذا الانفتاح اللبرالي مشروع تطوير وسط مدينة عمان، في منطقة العبدلي، الذي بوشر العمل به في عام 2004 بواسطة مؤسسة مشتركة بين القطاعين العام والخاص: موارد.

يعرض المخطط الشمولي لعمان الكبرى، الذي أعلن عنه في عام 2008، قطع أراضٍ محاذية لممرات تنموية متاحة للمستثمرين الدوليين، وهو يهدف إلى تزويد المدينة بشبكة وسائل نقل عام متطورة، وفي مسارات مخصصة لها حصريا.

في الوقت نفسه، أعلن الملك برنامجا طموحا لبناء 100000 وحدة سكنية للأسر ذات الدخل المحدود. توقف العمل في هذه المشاريع في عام 2011، بتأثير موجة الاحتجاجات الاجتماعية والسياسية.

يعرض هذا الفصل السياسات الحضرية المتتالية التي جربها الاردن للسيطرة على النمو الحضري ولتطوير الخدمات العامة بمشاركة المواطنين، وبالتالي تعزيز الديمقراطية المحلية. كما يعرض التحديات التي تواجه المجالس البلدية بسبب وجود جيوب الفقر في المدن الاردنية، والسياسات المتعاقبة التي اعتُمِدت لاعادة تأهيل الاحياء العشوائية.

نستعرض فيما يأتي الإطار العام للبلديات، إضافة إلى وسائلها في الفعل واتّخاذ الإجراءات. ثم نقدّم تحليلا وظيفيا وعمرانيا للتجمعات السكانية الرئيسية الثلاثة: عمّان – الرصيفة – الزرقاء، وإربد، والعقبة.

[Excerpted from Atlas of Jordan: History, Territories, and Society, edited by Myriam Ababsa, by permission of the editor. © Presses de l’Ifpo, 2013. For more information, or to access the complete text in English or Arabic, click here.]

![[Cover of Myriam Ababsa, \"Atlas of Jordan: History, Territories, and Society\"]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/AtlasofJordancover.jpg)